MIKÄ ON ASFI-virus? Se on afrikansian kuumevirus ja aiheuttaa verenvuotokuumetta ja johtaa korkeaan kuolleisuuteen porsaissa. tauti ei tartu ihmisiin. Viruksest löytyy 548 hakuvastausta PubMed kirjqastosta: Paljon uusia tutkimuskai tältä vuodelta.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=ASFV

Wikipediasta ainakin löytää jotain tietoa englanniksi. Liitän sitaatin tähän blogiin, koska en ole tästä virukssta aiemmin lukenut mitään.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_swine_fever_virus

Evira (Elintarvikevirasto) antaa luetteloa teistä, joista tätä virusta voi päästä leviämään Suomeen. Turismi on yksi syy. Myös elintarvikeimport. Sitäpaitsi pehmeät punkit voivat kuljettaa sitä toimien vektorina

https://www.evira.fi/elaimet/elainten-terveys-ja-elaintaudit/elaintaudit/siat/afrikkalainen-sikarutto/ala-tuo-afrikkalaista-sikaruttoa-suomeen/

Asfivirus, ASFV, on ds-DNA- virus, joka replikoituu solun sytoplasmassa ja kuuluu sukuun

ASFARVIRIDAE Se infektoi porsaita, pahkasikaa, ja pensassikaa sekä Ornithoros-punkkia. ASFV onkin ainoa dsDNA virus joka käyttää vektorina arthropodaa.. Virus aiheuttaa sikakarjan porsiassa verenvuotokuumetta. Jotkut virusisolaatit ovat viikossa tappavia, mutta muissa eläinlajeissa infektio ohittuu ilman ilmeista tautia. Sub-saharan alueella virus on endeeminen ja kiertää luonnossa sykliään vektoripunkin ja willisikojen, pensassikojen ja pahkasikojen porsaiden välillä. Tauti ilmeni ensikertaa kun eurooppalaiset asukkaat toivat possuja viruksen endeemiselle alueelle ja sen takia tauti on hälyttävästi leviämässä oleva infektiotauti,

emerging infectious disease.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_swine_fever_virus

African swine fever virus (

ASFV) is the causative agent of African swine fever (ASF). The virus causes a

haemorrhagic fever with high mortality rates in pigs, but persistently infects its natural hosts, warthogs, bushpigs, and soft ticks of the

Ornithodoros genus, with no disease signs.

[1]

ASFV is a large, double-stranded

DNA virus which replicates in the

cytoplasm of infected cells, and is the only member of the

Asfarviridae family.

[2] ASFV infects domestic

pigs,

warthogs and

bushpigs, as well as soft

ticks (

Ornithodoros), which likely act as a

vector.

[1]

ASFV is the only known virus with a double-stranded DNA genome transmitted by

arthropods.

The virus causes a lethal haemorraghic disease in domestic pigs. Some

isolates can cause death of animals within as quickly as a week after

infection. In all other species, the virus causes no obvious disease.

ASFV is endemic to

sub-Saharan Africa

and exists in the wild through a cycle of infection between ticks and

wild pigs, bushpigs, and warthogs. The disease was first described after

European settlers brought pigs into areas endemic with ASFV and, as

such, is an example of an '

emerging infectious disease'.

ASFV -virus on ikosahedrinen ja lineaarissa genomissa on vähintään 150 geeniä. Viruksessa on piirteitä muista isoista dsDNA-viruksista kuten isorokosta, indoviruksesta ja mimiviruksesta. Replikaatio tapahtuu kohdesoluissa monosyyteissä ja makrofageissa. Viruksen pääsytapa soluun on vielä selvittämättä.

Virology

Diagram of ASFV and other members of Asfarviridae

ASFV is a large, icosahedral, double-stranded

DNA virus with a linear

genome containing at least 150 genes. The number of genes differs slightly between different isolates of the virus.

[3] ASFV has similarities to the other large DNA viruses, e.g.,

poxvirus,

iridovirus, and

mimivirus. In common with other

viral haemorrhagic fevers, the main target cells for replication are those of

monocyte,

macrophage

lineage. Entry of the virus into the host cell is receptor-mediated,

but

the precise mechanism of endocytosis is presently unclear.

[4]

The virus encodes enzymes required for replication and transcription

of its genome, including

elements of a base excision repair system,

structural proteins, and many proteins that are not essential for

replication in cells, but instead have roles in virus survival and

transmission in its hosts.

Virus replication takes place in perinuclear

factory areas. It is a highly orchestrated process with at least four

stages of transcription—immediate-early, early, intermediate, and late.

The majority of replication and assembly occurs in discrete, perinuclear

regions of the cell called virus factories, and finally progeny virions

are transported to the plasma membrane along

microtubules where they

bud out or are

propelled away along

actin

projections to infect new cells. As the virus progresses through its

lifecycle, most if not all of the host cell's organelles are modified,

adapted, or in some cases destroyed.

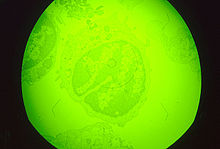

Macrophage cell in early stages of infection with ASFV

Assembly of the icosahedral

capsid occurs on modified membranes from the

endoplasmic reticulum. Products from proteolytically processed polyproteins form the core shell between the internal membrane and the

nucleoprotein core.

An additional outer membrane is gained as particles bud from the

plasma membrane.

The virus encodes proteins that inhibit signalling pathways in infected

macrophages and thus modulate transcriptional activation of

immune response genes. In addition, the virus encodes proteins which inhibit

apoptosis of infected cells to facilitate production of progeny virions. Viral membrane proteins with similarity to cellular

adhesion proteins modulate interaction of virus-infected cells and extracellular virions with host components.

[2]

Genotypes

Based on sequence variation in the C-terminal region of the

B646L gene encoding the major capsid protein p72, 22 ASFV genotypes (I–XXII) have been identified.[5]

All ASFV p72 genotypes have been circulating in eastern and southern

Africa. Genotype I has been circulating in Europe, South America, the

Caribbean, and western Africa. Genotype VIII is confined to four East

African countries.

Evolution

The virus is thought to be derived from a virus of soft tick (genus

Ornithodoros) that infects wild swine, including

giant forest hogs (

Hylochoerus meinertzhageni), warthogs (

Phacochoerus africanus), and bushpigs (

Potamochoerus porcus).

[6] In these wild hosts, infection is generally asymptomatic. This virus appears to have evolved around

1700 AD.

This date is corroborated by the historical record. Pigs were initially domesticated in North Africa and Eurasia.

[7]

They were introduced

into southern Africa from Europe and the Far East

by the Portuguese (300 years ago) and Chinese (600 years ago),

respectively.

[8] At the end of the 19th century, the extensive

pig industry in the native region of ASFV (

Kenya) started after massive losses of cattle due to a

rinderpest outbreak.

Pigs were imported on a massive scale for breeding by colonizers from

Seychelles in 1904 and from

England in 1905. Pig farming was free-range at this time.

The first outbreak of ASF was reported in 1907.

Signs and symptoms

Reddening of the ears is a common sign of African swine fever in pigs.

In the acute form of the disease caused by highly virulent strains,

pigs may develop a high fever, but show no other noticeable symptoms for

the first few days.

[9] They then gradually lose their appetites and become depressed. In

white-skinned pigs,

the extremities turn blueish-purple and hemorrhages become apparent on

the ears and abdomen. Groups of infected pigs lie huddled together

shivering, breathing abnormally, and sometimes coughing. If forced to

stand, they appear unsteady on their legs. Within a few days of

infection, they enter a comatose state and then die. In pregnant sows,

spontaneous abortions occur. In milder infections, affected pigs lose

weight, becoming thin, and develop signs of pneumonia, skin ulcers, and

swollen joints.

[10]

Diagnosis

The clinical symptoms of ASFV infection are very similar to classical swine fever virus, and the two diseases normally have to be distinguished by laboratory diagnosis. This diagnosis is usually performed by an

ELISA or isolation of the virus from either the blood, lymph nodes, spleen, or serum of an infected pig.

[10]

History

The swelling around the kidneys and the muscle hemorrhages visible here are typical of pigs with African swine fever.

The first outbreak was retrospectively recognized as having occurred in 1907 after ASF was first described in 1921 in Kenya.

[11] The disease remained restricted to Africa until 1957, when it was reported in

Lisbon,

Portugal.

A further outbreak occurred in Portugal in 1960. Subsequent to these

initial introductions, the disease became established in the Iberian

peninsula, and sporadic outbreaks occurred in

France,

Belgium, and other European countries during the 1980s. Both

Spain and

Portugal had managed to eradicate the disease by the mid-1990s through a slaughter policy.

[12]

Cuba

In 1971 an

outbreak of the disease occurred in Cuba, resulting in the slaughter of

500,000 pigs to prevent a nationwide animal epidemic. The outbreak was

labeled the "most alarming event" of 1971 by the United Nations Food and

Agricultural Organization.

Conspiracy theory

Six years after the event the newspaper

Newsday, citing untraceable sources,

[13][14] claimed that with at least the tacit backing of U.S.

Central Intelligence Agency officials, operatives linked to anti-Castro

terrorists allegedly introduced African swine fever virus into

Cuba

six weeks prior to the outbreak in 1971, for the purposes of

destabilizing the Cuban economy and encouraging domestic opposition to

Fidel Castro.

The virus was allegedly delivered to

the terrorists from an army base

in the Panama Canal Zone by an unnamed U.S. intelligence source.

[15][16]

The Caribbean

ASFV crossed the

Atlantic Ocean, and outbreaks were reported in some Caribbean islands, including the

Dominican Republic. Major outbreaks of ASF in Africa are regularly reported to the World Organisation for Animal Health (previously called

L'office international des épizooties).

Eastern and Northern Europe

Outside Africa, an outbreak occurred at the beginning of 2007 in

Georgia, and subsequently spread to

Armenia,

Azerbaijan,

Iran,

Russia, and

Belarus, raising concerns that ASFV may spread further geographically and have negative economic effects on the swine industry.

[12][17][18]

In August 2012, an outbreak of African swine fever was reported in

Ukraine.

[19] In June 2013, an outbreak was reported in

Belarus.

[20]

African swine fever had become 'endemic' in the Russian Federation

since spreading into the North Caucasus 'in November 2007, most likely

through movements of infected wild boar from Georgia to (Chechnya)',

said a 2013 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization, a

United Nations agency.

[21]

The report showed how the disease had spread north from the Caucasus to

other parts of the country where pig production was more concentrated

the

Central Federal District (home to 28.8% of Russia's pigs) and the

Volga Federal District

(with 25.4% of the national herd) and northwest towards Ukraine,

Belarus, Poland and the Baltic nations. In Russia, the report added,

the

disease was 'on its way to becoming endemic in

Tver oblast'

(about 106 km north of Moscow—and about 500 km east of Russia's

littoral neighbours on the Baltic. Among the vectors for the spread in

Russia of African swine fever virus was the 'distribution' of 'infected

pig products' outside affected (quarantined and trade restricted) areas,

travelling large distances (thousands of kilometers) within the

country.

'Wholesale buyers, particularly the military food supply system, have

been implicated multiple times in the illegal distribution of

contaminated meat' were vectors for the virus's spread, said the Food

and Agriculture Organization report—and evidence of that was 'repeated

outbreaks in

Leningrad oblast'. The report warned that 'countries immediately bordering the

Russian Federation, particularly

Ukraine,

Moldova,

Kazakhstan and

Latvia,

are most vulnerable to [African swine fever] introduction and endemic

establishment, largely because the

biosecurity of their pig sector is

predominantly low.

Preventing the spread of [African swine fever] into

Ukraine is particularly critical for the whole pig production sector in

Europe.

Given the worrisome developments in the Russian Federation,

European countries have to be alert. They must be ready to prevent and

to react effectively to [African swine fever] introductions into their

territories for many years to come'...To stop the virus's spread, 'the

current scenario in the Russian Federation suggests that [prevention]

should be particularly stressed at the often informal backyard level and

should involve not just pig keepers, but all actors along the whole

value chain—butchers, middlemen, slaughterhouses, etc...They need to be

aware of how to prevent and recognize the disease, and must understand

the importance of reporting outbreaks to the national authorities...It

is particularly important that [African swine fever]-free areas remain

free by preventing the [re]introduction of the disease and by swiftly

responding to it when it occurs'.

In January 2014, authorities announced the presence of African swine fever in Lithuania and Poland,[22] in June 2014 in Latvia, and in July 2015 in Estonia.[23]

Estonia in July 2015 recorded its first case of African swine fever in farmed pigs in

Valgamaa county on the country's border with Latvia. Another case was reported same day in

Viljandi county, which also borders Latvia. All the pigs were culled and their carcasses incinerated.

[24]

Less than a month later, almost 15,000 farmed pigs had been culled and

the country was 'struggling to get rid of hundreds of tons of

carcasses'. The death toll was 'expected to rise'.

[25]

Latvia in January 2017 declared African swine fever emergency in

relation to outbreaks in three regions, including a pig farm in

Krimulda region, that resulted in a cull of around 5,000 sows and piglets by using gas.

[26][27] In February another massive pig cull was required, after an industrial scale farm of the same company in

Salaspils region was found infected, leading to a cull of about 10,000 pigs.

[28]

Czech republic in June 2017 recorded its historically first case of African swine fever.

[29]

Alternative theory

The appearance of ASF outside Africa at about the same time as the emergence of

AIDS led to some interest in whether the two were related, and a report appeared in

The Lancet supporting this in 1986.

[30] However, the realization that the human immunodeficiency virus (

HIV) causes

AIDS, discredited any potential connection with ASF.

See also

- Animal viruses

- Oma kommentti. Mitä tulee sian kasvatukseen ja sianlihan syömiseen, olen samaa mieltä kuin Mooseksen laki. Jalostetut possut ja siat ovat immuniteetiltään heikompia kuin luonnolliset vastineet ja suuri määrä tekee niistä vain ihmiskuntaan iskevien viruksien kiertoon ison soveltuvan altaan.

- Miksi niitä sitten on olemassa, arvelen että kudoksensiirtotarkoituksiin, koska kudos on lähellä ihmisen kudosta. ja insuliinin tekoa varten, ehkä muitakin erityisiä kudoksia tai molekyylejä voidaan hyödyntää vaikka semisynteeseihin.

- On periaate allergioissa että jos jotain lääkettä annetaan sekä ihon kautta , suun kautta että parenteraalisti , seuraa helposti allergisia reaktioita. Samoin jos esim käytetään sikaperäistä siirrettä tai insuliiniä ja sitten vielä tai ennen sitä syödään sikaa, voidaan saada vasta-aineita siirrettä ja insuliinia kohtaan helpommin. Arvelen.

- Mitä tulee eläinten teurastukseen, en ole vastaan seemiläisten tuhatvuotista perinnettä, jossa veren määrää kudoksessa saadaan laskemaan erittäin tehokkaasti , sillä veressä voi olla paljon ihmiselle epäsuotuisia tekijöitä jos sitä jää hajoamaan kudokseen

- Mitä tulee Pietarin taivaalliseen näkyyn kaikenlaisesta ravinnosta, siinä ei mainittu possuja. muta tässä en käy saivartelemaan, sanoinpa vain mikä on mielestäni ihmiskuntamitassa terveellistä, toisaalta ihmiskunnassa on paljon animaalisen proteiinin puutetta,

- Tässä olen vain teoretisoinut Mooseksen lain kohdan mahdollista merkitystä, kun kielletään syömästä sikaa.

- (Lampaan ja vuohen aksvatus voisi olla hyvä korvike ja varsinkin jos lampailla on kontrolloitua laidunta ja vihreää rrehua , nekin pysyvät terveinä paremmin kuin enenn vanhaan)